For those who thought their Insider account was broken … sorry, it was because I had started the post and then my power went out for the next ten hours! Californian infrastructure …

OK, so, the biggest piece of non-news this week aside from clarity on the cybersecurity situation was probably the (unsubstantiated) report that Alibaba and Tencent may be opening up to each other’s walled gardens. I say unsubstantiated because all of the Chinese media say that they were not able to get any confirmation, even unofficially. Not even the great Latepost, or its lesser competitor, Techplanet. But, confirmation isn’t really important here, because it’s really not even a news item at all, having been rumored for months, and taking a somewhat solid form in April when a Hema mini program (still mostly non-functional, apparently only accessible in very limited areas) appeared on WeChat. Nonetheless, it would be truly a phenomenally big happening when it does take place, so, this is a brief note on what that could mean.

Firstly, let’s step back in time to August 1, 2013 and note that it was Alibaba, NOT WeChat, who first started the mutual (total) ban. That’s because Jack Ma understood the threat WeChat truly posed as core communication infrastructure.* That was also right before WeChat launched WeChat Pay (which happened just a few days after the ban on August 5) and so I’m sure Alibaba was aware of that and wanted to preempt. I mean … of course Jack understood the gravity of the situation … he had already invested in Weibo in April 2013 back when it still had the opportunity to become a strong contender to WeChat, and of course, not satisfied with just one play, he also launched the ill-fated WeChat clone Alibaba Laiwang in September 2013. In hindsight, neither of those moves made a difference, but at the time, they were some of the best moves Jack had available.

But OK, back to August when the ban happened … it wasn’t completely out of nowhere either. Tencent was of course watching the Weibo investment, too, and Pony Ma, likewise no fool, knew that Alibaba was on high alert and was going to attack with all it had. So you could say that WeChat made the first clear aggression on July 26, 2013, when it banned Taobao’s official account. But that’s still much less severe than Alibaba’s August 1 action of banning all links coming from WeChat. After that though, it quickly escalated to full scale war. Either way … it was clear that at the time, Alibaba felt greater threat from WeChat than vice versa. And the big question today is … is that still the case 8 years later?

Well, yeah. There’s a lot of evidence that YES, it is still the case 8 years later.

-

Alibaba still dominates e-commerce, at least relative to WeChat. It’s not just that it still has an over 50% market share. It’s still where brands break out. When I did our first episode on DTC brands in China, a friend at Alibaba corrected me … “you know Rui, in China we don’t call it DTC really, we call it Taobao brand 淘品牌.” Two years later, while people are using DTC more frequently now (partly because some of these brands have a notable offline presence), if we are referring to an online brand, they still have to win Taobao / Tmall. That’s what Perfect Diary did, and that’s the predominant strategy of most emerging brands, even drink makers like Genki Forest. Yes, there are more and more “Douyin brands” now, but there are definitely no WeChat brands, mini program or not. Remember … WeChat is first and foremost a private communication channel!

-

What that dominance in ecommerce specifically translates to is in all the steps closest to the final transaction, but not at the top of the funnel, where all the discovery is happening. Using China tech parlance, Alibaba doesn’t have any “self-generating high-frequency traffic” a la a WeChat or Douyin. Whatever Alibaba had feared would come to pass way back in 2013 … has pretty much come to pass. They remain a dominant destination, but they’re having to spend more meeting where users are at, such as on Douyin ($1.4Bn+ last year, doubling this year) to get them to come there. Alibaba is of course fighting back with ecommerce livestreaming, Gaode Mapping, and all other aspects of local services, but none look like they’re going to massively tip the scales in Ali’s favor. They are incremental improvements at best, and if well-executed collectively, capable of changing Ali’s position, but probably not on their own.

-

Unlike Douyin, however, which is conceived of as an advertising platform first and foremost, WeChat does not have many ways for Alibaba to spam users at scale. It doesn’t have advertising inventory within the core communication panel, and only a little bit within Moments. Mini programs are amazing, but do not allow notifications (edit: as of the beginning of the year, limited service messages are allowed), and while one can freely spam them within every part of WeChat, one cannot spam them programmatically, or with any kind of priority, as they are entirely “people-powered,” which is the way WeChat was made. How about Official Accounts and Channels, you ask? Sure, but that already works, right? It either already directs to Alibaba apps (via a copy-paste code) or to branded mini programs (if made by the brand directly).

-

So unless things change and somehow WeChat allows for deeplinks from other apps to open up that app or prompt a download, something it’s been quick to ban even with other Tencent apps … we are really just talking about opening up mini programs to Alibaba and WeChat Pay to Taobao / Tmall. Edit: you can now open up the full app from WeChat. Which means that there are at least two questions:

-

Does Alibaba get a lot more users or incremental GMV from mini programs? I don’t know about users, with Alibaba at 925mm MAU already … but it makes sense that there could be incremental GMV, from just higher conversion from WeChat traffic. With such a large base, obviously, it can be significant. I’m sure someone has some reasonable assumptions on this, but whatever gain happens here, probably pales in comparison to the “additional GMV” to WeChat, which is starting off at 0 contribution from Alibaba. Which makes me think that the more important question is …

-

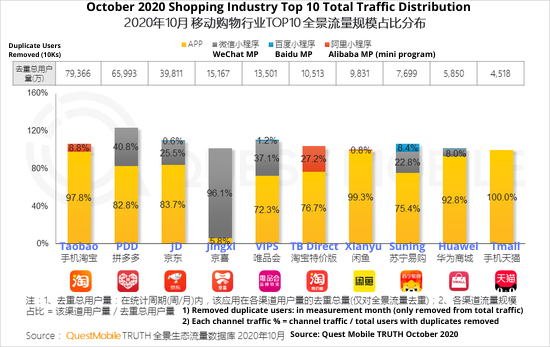

What is the benefit to WeChat? Well, since we are starting from 0 here … possibly much greater. So again, assuming that this “openness” is only going to take place at the mini program level … take a look at what the mini program penetration looks like for the top shopping apps as of October, 2020:

-

Obviously the Alibaba apps have no gray (WeChat mini programs), but JD, PDD and VIPS, even the Alibaba-affiliated Suning have over 20% traffic coming from mini programs! (And it’s FAR greater for other categories, by the way, ~50% for food delivery and ~95% for courier services, but ele.me is already on WeChat mini programs …).

-

Yes, I’m aware that WeChat is not valued on GMV. It’s also not necessarily the case that all WeChat GMV will be on WeChat Pay. But for sure some part of it will be, and add to that the fact that WeChat Pay should be allowed in Alibaba’s apps (that seems really difficult to deny and claim antitrust adherence), and it seems to me that WeChat benefits more here from a more loving relationship with Alibaba. Which is … you guessed it, as Jack had always feared.

So to summarize …

Alibaba gets:

-

WeChat mini program access, which likely increases users marginally, and GMV perhaps a bit more than users, but no real systematic way to manipulate user engagement / growth, due to the fact that WeChat is not designed as an advertising platform

-

Yes it can obviously do the Pinduoduo strategy, which is a subsidy play but on WeChat’s lightning fast social infrastructure (and which Jingxi has executed on as well), but is that what investors want to see? I certainly wouldn’t, but maybe I’m too conservative …

-

Most importantly though, doesn’t this makes WeChat stronger?? Now there really is just ByteDance that’s not on WeChat. And is that what Alibaba wants? Not that there’s any competition, but it kinda feels like Alibaba can kinda kiss its own mini program ecosystem good bye then …

-

Which is why I think Alibaba is thinking about what to put on WeChat very carefully, and starting off with a tiny experiment like Hema …

WeChat gets:

-

Alibaba users to complete transactions within WeChat via mini programs! Potentially 20%+ of them for the shopping apps and 50%+ for local services not already on the platform (ele.me is), and I don’t think that’s even steady state, that’s actually growing. Some of them will probably use WeChat Pay. (I’m not sure that they can be forced to use WeChat Pay.) Either way, WeChat is gaining from 0 Alibaba activity / GMV to potentially a lot, and that just seems like a much, much bigger win to me …

As for the other players:

-

Pinduoduo is for sure the most impacted, if Taobao Direct, which is the only one with significant MAU growth ahead of it (it’s just barely over 100mm as of Q1 2021) can get access to WeChat mini programs, because let’s face it, anyone can run a subsidy campaign, and with its unbranded marketplace, what exactly is keeping users there? Besides the hongbaos? And we already see above that Jingxi is almost entirely mini programs … and that in general the lower the price point, the higher the % of min program penetration, which for Pinduoduo itself is ~40%. So … quite scary actually.

-

JD is likely much less impacted, due to its lesser reliance on WeChat MP, its higher brand differentiation, its logistics moat, blah blah. But maybe Jingxi (MAU: 142mm as of Nov. 2020) gets bogged down more. Although, if you believe the company, it’s not really trying to compete on speed there, so maybe it doesn’t matter …

-

Kuaishou, Meituan et al. may face competition from Alibaba’s apps, if the company decides to move everything onto WeChat. But would it? I’d be reluctant to make such a big decision knowing that I could really, really, become beholden to WeChat in a big way … ie having 50% of ele.me be on WeChat mini programs. Really?

-

ByteDance is Tencent’s other nemesis and one that it proactively blocked (unlike Alibaba, haha) because ByteDance is even more top-of-funnel than WeChat, in many ways. The interesting question is does all this opening up extend to ByteDance and WeChat as well. I’d imagine it will, eventually, but in that respect WeChat is much more evenly matched, and I’m less decided that WeChat will win, although it still has a good chance, because, well, I’m almost tired of repeating it, but it’s a communications tool and very difficult to topple entirely (but certainly ByteDance can cut off its growth into more public networks).

Agree? Disagree? Let’s debate … !

*I should note here that the internet never forgets, and there are plenty of things Jack said about WeChat — “it’s not WeChat that threatens us, it’s us that threatens WeChat” or “WeChat had a good hand, but played it poorly” etc. — that make it seem like he didn’t think highly of WeChat, but just judging not by his words but his actions, I think that he was pretty damn scared. Of course, Jack being Jack, he probably also thought that he could do WeChat one better — and it’s true, why would a company led by notorious introverts be able to do better at a social product than flashy Jack’s army — but I’d argue that a product like WeChat just really isn’t in Alibaba’s operationally intensive DNA to make …