Extra Buzz 012: One Trillion Yuan ($136Bn) in 18ish Days

Hi Extra Buzzers,

I hope everyone is doing well despite the continued turmoil -- covid19 related and otherwise -- in many parts of the world. Here in San Mateo County in the Bay Area, where I am, nearly everything has reopened. But nothing feels normal yet.

Here in the US, my social media was flooded with recognition of Friday as Juneteenth, which celebrates the emancipation of those who had lived under slavery in this country. Many Silicon Valley tech companies made it a paid holiday, beginning with Twitter and Square, but also including TikTok, which even made a separate page for the day. Is it just me or is that impressive decision making speed for a Chinese internet company? Anyway, in my Chinese feed, however, an entirely different “holiday” celebration was underway, and that is, of course, the 618 Shopping Festival, initially created by JD.com for its company anniversary, but now an industry-wide frenzy that has every ecommerce employee I know working overtime for months in preparation. And here are a few thoughts I have on the news. Would love to hear your feedback! Please send it along!

Best,

Rui

One Trillion Yuan (or $136Bn) in 18ish Days

We already know that China’s e-commerce market is the largest in the world. There are a few numbers out there, but let’s call it $1.5Trn or so in sales in 2019 (via the more conservative McKinsey), which makes it roughly $10Trn Chinese Yuan when converted. Which means that, for 618, just JD and Alibaba alone managed to rack up in GMV an amount that is roughly 10% of the total sales the entire industry made all of last year. Which is why it is headline news all over the world, especially in post-pandemic China, where lockdowns were lifted over two months ago. Everyone was holding their breath to see how much consumer confidence had “recovered,” or even grown, when it came to shopping online.

As you can see from this promotional poster, the 618 Shopping Festival actually started on 6/1 and lasted through the 20th. Preorders actually began on May 25! Officially, it ended on 6/18, but additional promotions go through even Father’s Day the 21st.

If you’ve been listening to Tech Buzz for a while, of course, you’ll note that the comparison above is a fallacious one. Of course I wouldn’t make that kind of facile mistake! In our Episode 29 on Single’s Day from back in 2018, we explained the slipperiness of the metric that is known as GMV. Not only is it not at all an indication of actual revenues generated, but it doesn’t even represent sales as most of us would probably define it in everyday conversation. Even CNBC has wised up to this discrepancy and notes that JD’s staggering $38Bn number is only the total value of orders placed, “regardless of whether the goods are sold, delivered or returned.” I thought research analyst Steven Zhu at Pacific Epoch put it well when he said to Bloomberg: ““It’s just what I call paid-GMV for all the platforms. It’s the time that people have to have a good number after the coronavirus, so they just do it at whatever the cost.” Exactly. Even though everyone knows the ultimate meaninglessness of these numbers, the fact that they can be tallied in real-time and most importantly, compared both historically and across different platforms (with few variations) means that until a simpler headline number is invented, I predict that we will be stuck with GMV readouts for a bit longer yet. For these time-bounded, nation-wide competitions anyways. (On a business as usual basis, Alibaba abandoned reporting its GMV back in 2016, and JD followed suit in early 2019. It still does so annually, however.)

Aside from the mind-bogglingly large and unreliable GMV number though, which seems to have everyone proclaiming that consumer demand has roared back to life, what are some other important takeaways from this year’s 618 that are different from seasons past? Here are a few, and the background / context as well as my thoughts on each:

1. Impact of Covid. The specter of covid19 continues to linger and continues to cast its shadow over everything in China these days. On June 15, a new cluster of cases was discovered in Beijing, and the city has gone back under partial lockdown. While life feels like it’s mostly “returned to normal” for many of my friends, the same cannot be said for the many millions of unemployed as a result of the pandemic. China’s economy contracted 6.8% the first quarter, and it’s abandoned giving a GDP target for the rest of the year, for the first time ever. Analysts think that 80mm people are out of work, a number that’s hard to verify because China’s methods of calculating unemployment places so many restrictions and such a burden on the unemployed citizen to self-report that it’s nearly meaningless. But even those numbers have seen a spike. Either way, this is a real problem.

2. The Government’s Response. In the beginning of June, there was brief fervor over Premier Li Keqiang’s words that the “street stall economy” could help the country get back on track, especially for the unskilled and unemployed, in an apparent reversal of the last few decades of eradicating exactly such practices in Chinese cities. This statement was then immediately walked back by state media and also defiantly denounced by cities like Beijing and Shenzhen. I bring up this news only because e-commerce remains the only non-controversial and indeed, greatly applauded solution that I’ve seen to solving these problems. If there is a downside, I haven’t seen it mentioned. Sure, conflicts still arise where the consumer’s rights are infringed upon -- fake goods being the primary culprit -- but as a distribution channel, China is all in on ecommerce.

This is evident in state media coverage. Whereas last year the focus was on the consumer side, a lot of hoopla made over consumption upgrade -- more people buying large screen TVs! smart devices! -- this year, understandably, the focus was on how ecommerce is helping small businesses find new avenues of survival post-covid. Especially livestreaming e-commerce, which, as we’ve noted, has been personally endorsed by President Xi Jinping as a good thing for rural China, allowing those even in the most remote places to connect with nationwide consumers. Of course, it’s also creating urban jobs as well. One district in Guangzhou is going as far as to dole out substantial housing subsidies for livestreaming ecommerce influencers to relocate into their neighborhood.

But they’re not leaving it up to just the professionals either. Over 300 city and town mayors and government officials of various ranks livestreamed on 618. One mayor had 6 livestreaming rooms open simultaneously … unclear if she was broadcasting to all at the same time (which happens by the way!). As has been noted, it’s not that these mayors are trying to become livestreaming influencers (I hope not?!), but that they are encouraged to experiment with the technology firsthand. Part of it is so that they can set an example for the rest of the town, and part of it is so that by having personal experience with the technology and business model, they are better equipped to make policies that make sense. It is all so new, after all. Covid has set a new race in motion and nearly everyone is starting at roughly the same level of readiness. Especially in 2020, which is supposed to be the year that China eradicates poverty, you most definitely don’t want to slide backwards, covid19 be damned. (If you’re stressed out for the officials … don’t be -- the official marker for poverty is just a bit over $1 a day, and last year it was already just 2 or 3% of rural residents who fell below this level.) Which naturally brings us to our next point ...

A mayor livestreams to help sell his village’s goods.

3. Selling Agricultural Goods. Ecommerce has long been touted as a way out of poverty in rural China, so it’s not like the awareness and infrastructure wasn’t already there. In fact, by 2018, there were already over 3200 so-called Taobao villages, or towns where there were at least ~$1.4mm USD of transactions annually and 100 e-commerce shops. But the vast majority are near industrial centers, something like 90% in the 6 coastal provinces, and a lot of these sellers are small-time manufacturers (oftentimes previously subcontractors) to their local brands, which run the gamut from furniture to fabrics, and are in fact, upon closer inspection, mostly not “food related products”. Although platforms like Pinduoduo have been making a lot of noise about agricultural products since at least early 2018 and indeed doubled down on that promise earlier this year with a proposed $7.1Bn plan over the next five years, there have been many reasons why this sector has not been as easy to grow. The biggest single factor being branding and marketing, followed by standardization, quality assurance, logistics, and the like. Now, I’m not saying that it hasn’t done well -- Pinduoduo in particular is saying that 15% of its GMV is now agricultural products -- but it’s requiring significant investment, as we’ve seen.

However, the advent of livestreaming has made this whole “branding” thing much easier for your farmers, who do not need to think about clever copywriting or put together fancy marketing assets. They are no longer just unmoving images on a webpage but real people who can take you, the viewer and prospective buyer, on a journey into their fields, products, and even personal lives. (I just watched a rural beekeeper go to her hives, for example, on Kuaishou, and even though I’d still be hesitant to put down an order because I’m paranoid about food safety, I’d be the first to admit that the barrier is much lower, because I’ve, you know, seen her bees.) Which is another difference that makes this year’s 618 different from years past … the focus on reporting agricultural goods GMV. Of course, this is not really a 618 trend as much as it is a nationwide, industry wide trend, with constant state media coverage devoted to the efforts the e-commerce platforms are devoting to this massive and particularly vulnerable population. Covid19 has accelerated the number of rural e-commerce vendors to 13mm, and in Q1 Pinduoduo saw 1 billion orders for agricultural products, an increase of 184%.

Again, the road is still long. As this 2019 article noted, while rural e-commerce sales has been growing like a weed -- the precovid projected CAGR for the next 5 years was 39% -- the transaction volume of agricultural products is just one-sixth of that, and was showing every sign of lagging even farther behind. We’ll see if the many (very expensive) infrastructure upgrades necessary to make the dream of farm-to-table come true in China can occur as quickly as the e-commerce giants are promising. (A lot of them overlap with the grocery delivery challenges that we discussed back in Tech Buzz Episode 58, such as cold chain and the like.) But … JD experienced a 165% growth on its platform this year during 618, and I can’t imagine that doesn’t continue for at least the rest of the year.

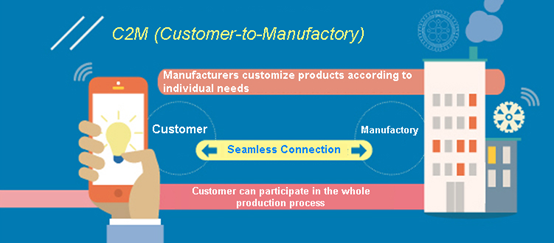

4. C2M (consumer-to-manufacturer). Another big trend this 618. Alibaba’s version, by the way, topped the Shopping appstore leaderboards and had 1mm new users on June 15th alone, as headlines everywhere screamed. Anyway, the best definition of C2M I’ve come across is this one in a Medium post: “Instead of manufacturers approaching the market with what they could produce, consumers collectively approach manufacturers with what they should produce.” It’s different from conventional pre-ordering in that consumers initiate the demand, whereas pre-ordering is primarily a method to manage cash flows and still otherwise looks quite similar to traditional retail where the manufacturer comes up with the product specs and finds buyers through marketing. It is also different from the typical just-in-time manufacturing in that again, the specs and demand for those products are not always consumer-initiated. However, as we will see, it can and usually does incorporate both of these concepts.

If you’re having trouble understanding what this could possibly mean, Alibaba’s Alizila has one of the better examples of C2M in this case study. Alibaba noticed via consumer searches that there was an increased interest, as a result of the pandemic, in high alcohol content car cleaning products, and thus contacted a manufacturer of car accessories to create a new product that would satisfy these evolving customer needs. The manufacturer then did use pre-ordering before the first batch of product shipped. The end result is win-win-win.

Pinduoduo, by the way, might be the biggest proponent of this concept and has been heavily marketing this as a key highlight of its business model since late 2018, when it supposedly began working with 1,000 contract manufacturers. My understanding is that it’s been around since much earlier than that, but either way, this is not a surprising business model to emerge out of China, which is still, after all, the Factory of the World, and a factory, by the way, that has been slowing down. Anyway, since at least two years ago, both Alibaba and JD have launched Pinduoduo clones, which are now increasingly being referred to as their C2M products.

It’s hard to distinguish how much of this is just marketing and very simple demand aggregation, and how much of it is real data-driven “demand shaping,” but expect to see a lot more of this mentioned in the future, as everyone jumps on this win-win-win bandwagon. Meanwhile, just like for agricultural products, I expect to see lots of consumer complaints and experiments gone awry as manufacturers step up to their new responsibilities as not just the supplier, but take over some of the previous “middle man” work as well (as do the platforms, of course). We’re working on a deep dive into this, by the way, so expect that in your mailboxes in the near future. All you need to know for now is that this is likely one of the big ways in which China e-commerce will further diverge from the US scene, if it all works as promised. There’s a lot of good one can imagine that comes out of not just a fully digitized supply chain, but one that’s linked to quantifiable customer demand as well.

An infographic explaining C2M as produced by ShanghaiTex in 2017.

Alright, so those are my thoughts on 618. Nothing too numbers-oriented, because as many others have pointed out, so much of that was due to heavy promotions and almost everything cited is GMV and thus not super meaningful, except as a directional indicator. Overall, the direction looks good for China e-commerce, which must be understood differently from the US, where it is mostly still just another retail distribution channel. Covid19 has accelerated the use of e-commerce for agricultural goods and for manufacturers directly, sellers who are not typically online nor do business directly with consumers. Some of this is due to naturally occurring economic forces, but at least some of it is or is going to be because of government intervention, as each community tries to recover from the devastation wrought by the pandemic. Infrastructure will need to be built out to support these new changes, but in the era of covid19, suddenly the math looks different. I’m pretty interested to see what happens next … !

PS For a thread on what “rural Chinese internet users look like” (as determined by compulsory education level, which is only K9 in China), check out this Twitter thread I made using Tencent Internet Research Center’s Data:

https://twitter.com/ruima/status/1272952949539389441