Extra Buzz #15: Chinese Tech Cos: We Need to Streamline Scaling and Systematize Innovation

Dear Tech Buzzers,

This newsletter is a bit different from prior ones. I’ve collected some of my notes for the ByteDance e-book I’m working on and tried to make a coherent piece out of one section where I’ve been spending the last few weeks: down a rabbit hole of how Chinese tech companies are upgrading their organizational design. It’s not easy to understand the difference between what’s reported / touted by the companies and what’s actually happening on the ground, so it’s involved a lot of personal interviews across different job functions and companies, and yet … I’m still looking at a pretty incomplete picture, so consider this a rough draft that will be improved upon as I gather more data points and perspectives.

But the central point I’m trying to share is that as the market matures and the “demographic dividend” from rapid smartphone adoption disappears, and with white-hot domestic competition, Chinese internet companies are thinking about and actively experimenting with not just what to make, but how to make it. How does one keep innovating? How does one out-compete well-funded, talented and determined players? If capital, talent and the sheer amount of hours thrown at the problem are equalized, what else can be re-jiggered? The very way work is done and companies are run is an obvious answer. There is, of course, inspiration from Silicon Valley, but there’s also the need to account for Chinese market and cultural characteristics, and so far, it seems that my pick for the most innovative company in China, ByteDance, has been most successful at merging these two disparate streams.

Thanks for bearing with me and reading this (very) early draft! Since I am comparing the experiments below with other tech companies operating outside of China -- that’s including Silicon Valley and elsewhere, of course -- would love any feedback / information on your personal experiences, if relevant!

Best,

Rui

First, The Middle Office Revolution Hype

One topic that’s been raging in Chinese media for much of the past year but has barely seen any mention in the West is the concept of the “middle office” or zhongtai 中台. Part of it is because it’s not that original; it is already implemented to varying degrees by ex-China tech companies like the FAANG. Part of it is because it is still emerging in China and its implementation by no means uniform. And finally, part of it is because Chinese internet giants face a different landscape -- the yawning greenfield market of an enterprise software market that is yet to truly emerge.

What problem are Chinese internet giants grappling with? Well, not really all that different from their Western peers. First of all, many of them are dealing with massive workforces -- Alibaba, for example, has over 117,000 employees -- and complex business lines. How do you manage everything efficiently and effectively? Secondly, the steady emergence of new threats even in fields that were once thought to be impenetrable -- like Alibaba’s dominance in e-commerce -- are forcing companies to answer the age-old question: how do we continue to innovate? How can we be as responsive to the market as possible and scale up quickly the new services we do discover?

One such proposed solution has been the middle office. For non-techies, May 21, 2019 was probably their introduction to the concept, because that’s when Tencent executives hyped up the concept during one of its Digital Ecosystem Summits and the media jumped all over it. These days, everyone in the business world has heard of zhongtai, but the first company to write a book about it was not Tencent, but its nemesis Alibaba.

As you can see, there was a great jump in that day’s Baidu searches for the term.

The story goes that all of this started in mid-2015 when Jack Ma took a group of Alibaba executives to visit the Finnish gaming company Supercell, creator of Clash of Clans (and now majority-owned by Tencent). As Supercell’s own webpage clearly states, it organizes itself in very small (10-17 developers), passion-filled teams that operate independently, free from bureaucracy and politics. In fact, the CEO believes that his job is to support the teams, and not to command them. These teams are called “cells,” and hence … Supercell. That’s right, this is a gaming company that is actually named after its organizational structure. But it’s also what the company believes is responsible for its continued innovation, especially its custom of actually hosting a party to celebrate its failures. Now, whether or not Jack really came up with the idea of smaller innovation teams supported by a bigger technology-enabled platform, I don’t know for sure. But what we do know is that Alibaba CEO Daniel Zhang wrote an internal email in December 2015 announcing the company-wide strategic initiative of “big middle office, small front office” 大中台,小后台. A particularly memorable and oft-used metaphor that is used to explain this rallying cry -- the front office are something like elite SEAL officers, on-the-ground with the user, responsive and agile, supported by a giant middle office, something akin to all the resources, solutions and intelligence of a central command center. For those of you who are more familiar with microservices, another relevant concept where services communicate with each other but can be developed, deployed and maintained separately, it might help to think of the zhongtai as a platform from which you request microservices for your product.

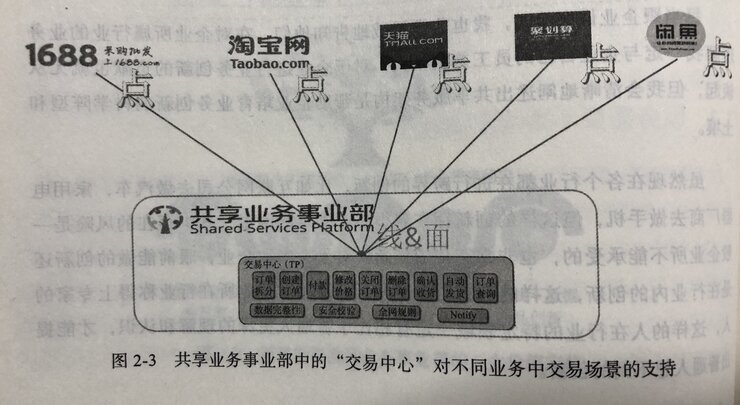

In fact, this became a highly acclaimed book written by one of the architects of Alibaba’s “middle office,” called Enterprise IT Infrastructure Evolution Strategy: Real Lessons from Alibaba’s Middle Office on Strategic Thinking & Structure, and was published in early 2017. As the book explained, in the first stage, the technical team of Taobao had to simultaneously support both the Taobao (C2C) and Tmall (B2C) marketplaces. This group was eventually renamed to “Shared Businesses Unit,” but was not considered a core business unit, and was constantly under pressure from both product teams. That is, until Alibaba created Juhuasuan, a marketing and flash-sales platform for selling on Taobao, Tmall, et al. In order the company decided that any connections Juhuasuan builds will have go through this “Shared Businesses Unit,” and it subsequently became a core business unit of Alibaba.

This decision turned out to be a great success. Juhuasuan was deployed in just a month and a half. It was so speedy precisely because of having to build on top of this “Shared Services Platform,” allowing it to re-use a lot of the technical and operational pieces that had already been built for Alibaba’s other assets, such as order management, customer service, payments, etc.

Alibaba’s various products plugging into the same shared services platform.

Then, ByteDance & the Platformization of Everything

As you might have guessed by now, zhongtai is how ByteDance organizes itself, and has organized itself, from the very beginning, though the term wasn’t in vogue then. I haven’t gotten around to confirming why Zhang Yiming pursued this from the get go, but given that Amazon is one of his most admired companies, it makes sense that platformization* -- both internal and external, and in fact, one leading to the other -- was the route he chose. (*This “rant” on Amazon’s platformization efforts is awesome. h/t Dan.)

In such an organization, a very small team builds a prototype (“the innovation”), and then tests it to achieve product market fit before it then is plugged into (or modified so as to be able to plug into) the zhongtai, a platform which has all of the company’s pre-built (technical) modules / pieces that have been built for previous initiatives, allowing the nascent project to scale up quickly and efficiently. That’s the idea, anyway, if things go well. In ByteDance, however, it’s not just the technical pieces that are platformized (the zhongtai), but a good chunk of the operations as well. If it is a repetitive task, even if it’s wholly internal facing such as customer discovery for new product development, it will become an accessible resource available to all. If it’s external facing, such as commercialization, it will become its own separate unit and service all relevant products. If it’a a technically repetitive task, then it will become part of the zhongtai.

It’s been reported that ByteDance’s zhongtai is composed of three parts: user growth, technology, and commercialization, corresponding to the three most important aspects of a product: acquisition, retention, and monetization. ByteDance’s moneymakers Toutiao and Douyin both work this way. In March 2019, ByteDance began building a “livestream middle platform.” It was speculated that the reason why livestreaming was getting its own “middle office” was because ByteDance was hitting a ceiling in its advertising business through Toutiao and Douyin. Livestreaming, as competitor Kuaishou and Alibaba had demonstrated, was capable of generating significant revenues, while being fundamentally different in its technology as well as business model from short video and advertising. In search of a new avenue of growth, ByteDance began centralizing the development of livestreaming for all of its video assets at the time: Xigua, Douyin and Huoshan.

I argue that while the primary purpose is to stabilize and most efficiently scale new and existing products, an obsession with platformization, much like their inspiration, Amazon, is also how they are able to keep the “product innovation” teams very small and agile, launching constantly, failing quickly, but also scaling quickly. By focusing on a very robust “middle office” layer whereby there is a huge focus on ease of integration, ByteDance (and other Chinese companies) make sure that the valuable talent that is most difficult to find / hire / develop can be most effectively and flexibly deployed across the company’s needs, versus being siloed into one product or business unit. This gives your talent the most leverage, but only if you truly have the flat corporate culture to support it. In the case of ByteDance, it does.

Not All Platforms Are Created Equal

In the course of trying to write about this topic -- I spoke to various friends and sources working at different large Chinese and US tech cos trying to understand how new products were really conceived of and scaled up, not just as reported in glowing magazine cover stories or as org charts revealed. Without going into too much detail about each, because that would easily be a book of its own or at least certainly someone’s dissertation, I have come out of the talks with a few takeaways.

You could have the platform, but if code was still siloed into “product” versus “platform,” then things would inevitably get unnecessarily complex and political as fights over ownership and individual KPIs erupt. Full transparency and accessibility is crucial, something ByteDance shares with Google.

Another frequent obstacle was when folks simply didn’t “platformize” enough of the technology and processes that they should have, usually due to objections from existing product owners who didn’t like to cede control. It is especially important to remember that these days, it is not just software that is repetitive, but a lot of the operations are as well (ie community management could be managed by the same unit across multiple products and best practices shared and quickly implemented). Chinese companies were quicker to spot these opportunities for non-tech solutions to be also centralized, in a sense.

Third, you could have the platform, but if you made integration very difficult because that was not your first priority then it would actually be a deterrent, not a benefit. Or if you made the threshold of success too high before platform resources could be invoked and applied.

Finally, if you didn’t treat it as a service that could be completely independent, then it was likely that you wouldn’t have built enough either ease-of-use / maintenance or robustness into it. Consequently, this building for an “external audience” is #5 of the reasons why Amazon was successful with its platformization efforts in the epic post I link above.

This last point is why, faced with the potential of tremendous upcoming growth in cloud services, Chinese tech companies are rushing to replicate the Amazon PaaS playbook by selling externally what they’ve developed internally. They are also motivated by the vacuum created by AWS’ limited presence in China, and Google’s complete absence. At the aforementioned DES in May 2019, Tencent Senior EVP Dowson Tong, head of the Cloud and Smart Industries Group (CSIG), sold the crowd hard on why they should be excited by and want to purchase Tencent’s suite of cloud services to build up their own zhongtai. Alibaba has been in this business for a while, and ByteDance, of course, has also launched its own cloud services platform: Volcano Engine. It just so happens, I think, that this also gives them the “platform-first” thinking that helps with internal collaboration, product scaling, and accelerating innovation.

PS We returned to our usual podcast format last week to talk about KE Holdings, China's latest mega-IPO on the NYSE. Our next ... Ant Group of course! Here's what's making the rounds on the Chinese interwebs about the company and the many billionaires it's creating:

Rui Ma 马睿同学

@ruima

Here's a happier tweet.

Viral image of "whole floor at Ant Group erupting in cheer." Why? Bc supposedly:

After IPO, Ant (& Alibaba) will generate:

13 ppl worth $2-$20Bn more

18 ppl $1-$2Bn more

21 ppl $0.1-$1B

6 ppl ~$100mm

= 58

"It is the sound of financial freedom." https://t.co/g4DHuqjkSw

3:28 PM - 27 Aug 2020

Have a great week!